Previous page

Back to articles index

So much for what's up there and what it looks like. How do

we go looking for it?

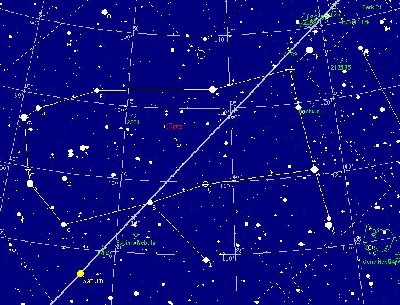

We

look on a star chart, which now is more likely to be computer sofware than a

book. And for the information that appears on them we have people like Charles

Messier and Pierre Mechain, and William, Caroline and John Herschel to thank.

They didn't know what M35, or Messier 35, at the top right of this view of Gemini

was. Or NGC2392, the Eskimo Nebula, close to the yellow dot showing the position

of Saturn that night. They discovered them, and compiled the Messier Catalogue,

which dates from the eighteenth century, and the General Catalogue of Nebulae,

which was rewritten into the New General Catalogue of Nebulae, or NGC, in 1888.

And now all we have to do is hit a few keys on a computer and we can find out

what's visible from our observing site and when, where it is and how big and

bright it is, so we can work out which bit of equipment we'll need to look at

it. You can even buy a telescope which will point itself straight at it so you

don't even have to know where to find it. Personally I think that spending an

hour looking for a galaxy in Virgo, then wondering if the one I've found is

actually the one I was looking for, is more fun. Computer guidance, or the 'go

to' facility, does have its place, but I wouldn't recommend it to a beginner.

The important thing to remember is that finding things for yourself isn't daunting.

To use a star chart you don't have to know every constellation. If you can recognise

the brighter stars of just a few, you can use them to find anything else.

We

look on a star chart, which now is more likely to be computer sofware than a

book. And for the information that appears on them we have people like Charles

Messier and Pierre Mechain, and William, Caroline and John Herschel to thank.

They didn't know what M35, or Messier 35, at the top right of this view of Gemini

was. Or NGC2392, the Eskimo Nebula, close to the yellow dot showing the position

of Saturn that night. They discovered them, and compiled the Messier Catalogue,

which dates from the eighteenth century, and the General Catalogue of Nebulae,

which was rewritten into the New General Catalogue of Nebulae, or NGC, in 1888.

And now all we have to do is hit a few keys on a computer and we can find out

what's visible from our observing site and when, where it is and how big and

bright it is, so we can work out which bit of equipment we'll need to look at

it. You can even buy a telescope which will point itself straight at it so you

don't even have to know where to find it. Personally I think that spending an

hour looking for a galaxy in Virgo, then wondering if the one I've found is

actually the one I was looking for, is more fun. Computer guidance, or the 'go

to' facility, does have its place, but I wouldn't recommend it to a beginner.

The important thing to remember is that finding things for yourself isn't daunting.

To use a star chart you don't have to know every constellation. If you can recognise

the brighter stars of just a few, you can use them to find anything else.

So let's consider what we need to look at all these lovely

planets and galaxies and clusters and nebulae.

Number One - Somewhere

to look from, though perhaps not here!

Try

to find somewhere reasonably dark but don't choose somewhere fifty miles from

home unless you live in the middle of London and have no choice. You'll only

end up staying home. Hills attract cloud, unless you live in a desert, and rivers

attract mist. If you can do your observing from your own garden so much the

better, and don't forget that you can use buildings, fences and trees to screen

lights. A lot depends on the type of observing you want to do. I can use binoculars

from my garden by sitting in a chair and using some convenient sheds to hide

street lights. To use a telescope I have to pack up and move out of the village,

using a barn to shield lights from a road junction. For astrophotography I leave

the country!

Try

to find somewhere reasonably dark but don't choose somewhere fifty miles from

home unless you live in the middle of London and have no choice. You'll only

end up staying home. Hills attract cloud, unless you live in a desert, and rivers

attract mist. If you can do your observing from your own garden so much the

better, and don't forget that you can use buildings, fences and trees to screen

lights. A lot depends on the type of observing you want to do. I can use binoculars

from my garden by sitting in a chair and using some convenient sheds to hide

street lights. To use a telescope I have to pack up and move out of the village,

using a barn to shield lights from a road junction. For astrophotography I leave

the country!

The bad and

the good

One thing it's almost impossible to get away from, anywhere,

is skyglow.This is the halo of light you see above towns and comes from all

the light from inefficient street lights, pretty globe lighting so favoured

in supermarket car parks, badly positioned security lighting and sports field

lights ending up in the sky instead of on the ground where it's needed. What

astronomers need is full cut off lighting - the type which is shielded to throw

all its light downwards. It's still no good if you're underneath it, but it

cuts sky glow completely. A lot of new motorway lighting is full cut off, and

the transition from a stretch of old lights - lots of sky glow, indifferent

light hardly reaching across the carriageways - to new lighting - a well lit

road with pitch blackness above - is remarkable. You'll know it if you've seen

it. All new lighting should be full cut off - it's not only good for astronomers,

it's environmentally friendly too - but sadly it isn't.

Wherever you go, whether it's a drive out of town or to the

bottom of your garden, you'll need to take with you finder charts for what you

want to look at, a red torch to read them by - white light will simply destroy

your dark adaption - a means of making notes and warm clothing. And don't stay

out too long. Go home while you're still warm and awake. There'll still be things

to look at on the next clear night.

Number Two - an

eye......like these would be nice!

Learn

to see faint objects and detail by using the rods in your eye - the low light

sensors - instead of the cones which are your daylight sensors. It's called

averted vision and all you have to do it look very slightly away from what you're

looking at. After a while it becomes completely subconscious. If you've ever

noticed you see things better in your peripheral vision at night, you've already

been using averted vision.

Learn

to see faint objects and detail by using the rods in your eye - the low light

sensors - instead of the cones which are your daylight sensors. It's called

averted vision and all you have to do it look very slightly away from what you're

looking at. After a while it becomes completely subconscious. If you've ever

noticed you see things better in your peripheral vision at night, you've already

been using averted vision.

Number Three - more

magnification.....and one of these would be nice too!

Start

with a good quality pair of binoculars. 10 or 12 by 50s are ideal. You need

a reasonable objective lens size but you don't need huge magnification. That

just adds weight, and even a fairly lightweight pair of binoculars can feel

very heavy very quickly when you're looking up. If they're still uncomfortable

use a deck chair or sun lounger. Use them to look at large objects like the

Pleiades and the Andromeda Galaxy.

Start

with a good quality pair of binoculars. 10 or 12 by 50s are ideal. You need

a reasonable objective lens size but you don't need huge magnification. That

just adds weight, and even a fairly lightweight pair of binoculars can feel

very heavy very quickly when you're looking up. If they're still uncomfortable

use a deck chair or sun lounger. Use them to look at large objects like the

Pleiades and the Andromeda Galaxy.

Then you might consider moving up to a telescope.

It has to be said that buying a telescope has never been easier,

but when all's said and done there are still only a few manufacturers - all

the multitude of shops sell the same range, so apart from accessibility if you

don't want to buy mail order, and a small variation in price, there's little

to choose between them. There are still, however, a lot of telescopes out there

to choose from, and most of them are not cheap. You'd think that buying the

right one for you should be easy.......

Next page

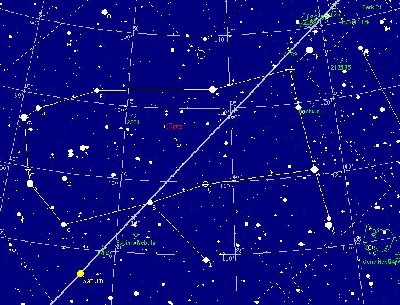

We

look on a star chart, which now is more likely to be computer sofware than a

book. And for the information that appears on them we have people like Charles

Messier and Pierre Mechain, and William, Caroline and John Herschel to thank.

They didn't know what M35, or Messier 35, at the top right of this view of Gemini

was. Or NGC2392, the Eskimo Nebula, close to the yellow dot showing the position

of Saturn that night. They discovered them, and compiled the Messier Catalogue,

which dates from the eighteenth century, and the General Catalogue of Nebulae,

which was rewritten into the New General Catalogue of Nebulae, or NGC, in 1888.

And now all we have to do is hit a few keys on a computer and we can find out

what's visible from our observing site and when, where it is and how big and

bright it is, so we can work out which bit of equipment we'll need to look at

it. You can even buy a telescope which will point itself straight at it so you

don't even have to know where to find it. Personally I think that spending an

hour looking for a galaxy in Virgo, then wondering if the one I've found is

actually the one I was looking for, is more fun. Computer guidance, or the 'go

to' facility, does have its place, but I wouldn't recommend it to a beginner.

The important thing to remember is that finding things for yourself isn't daunting.

To use a star chart you don't have to know every constellation. If you can recognise

the brighter stars of just a few, you can use them to find anything else.

We

look on a star chart, which now is more likely to be computer sofware than a

book. And for the information that appears on them we have people like Charles

Messier and Pierre Mechain, and William, Caroline and John Herschel to thank.

They didn't know what M35, or Messier 35, at the top right of this view of Gemini

was. Or NGC2392, the Eskimo Nebula, close to the yellow dot showing the position

of Saturn that night. They discovered them, and compiled the Messier Catalogue,

which dates from the eighteenth century, and the General Catalogue of Nebulae,

which was rewritten into the New General Catalogue of Nebulae, or NGC, in 1888.

And now all we have to do is hit a few keys on a computer and we can find out

what's visible from our observing site and when, where it is and how big and

bright it is, so we can work out which bit of equipment we'll need to look at

it. You can even buy a telescope which will point itself straight at it so you

don't even have to know where to find it. Personally I think that spending an

hour looking for a galaxy in Virgo, then wondering if the one I've found is

actually the one I was looking for, is more fun. Computer guidance, or the 'go

to' facility, does have its place, but I wouldn't recommend it to a beginner.

The important thing to remember is that finding things for yourself isn't daunting.

To use a star chart you don't have to know every constellation. If you can recognise

the brighter stars of just a few, you can use them to find anything else. Try

to find somewhere reasonably dark but don't choose somewhere fifty miles from

home unless you live in the middle of London and have no choice. You'll only

end up staying home. Hills attract cloud, unless you live in a desert, and rivers

attract mist. If you can do your observing from your own garden so much the

better, and don't forget that you can use buildings, fences and trees to screen

lights. A lot depends on the type of observing you want to do. I can use binoculars

from my garden by sitting in a chair and using some convenient sheds to hide

street lights. To use a telescope I have to pack up and move out of the village,

using a barn to shield lights from a road junction. For astrophotography I leave

the country!

Try

to find somewhere reasonably dark but don't choose somewhere fifty miles from

home unless you live in the middle of London and have no choice. You'll only

end up staying home. Hills attract cloud, unless you live in a desert, and rivers

attract mist. If you can do your observing from your own garden so much the

better, and don't forget that you can use buildings, fences and trees to screen

lights. A lot depends on the type of observing you want to do. I can use binoculars

from my garden by sitting in a chair and using some convenient sheds to hide

street lights. To use a telescope I have to pack up and move out of the village,

using a barn to shield lights from a road junction. For astrophotography I leave

the country!

Learn

to see faint objects and detail by using the rods in your eye - the low light

sensors - instead of the cones which are your daylight sensors. It's called

averted vision and all you have to do it look very slightly away from what you're

looking at. After a while it becomes completely subconscious. If you've ever

noticed you see things better in your peripheral vision at night, you've already

been using averted vision.

Learn

to see faint objects and detail by using the rods in your eye - the low light

sensors - instead of the cones which are your daylight sensors. It's called

averted vision and all you have to do it look very slightly away from what you're

looking at. After a while it becomes completely subconscious. If you've ever

noticed you see things better in your peripheral vision at night, you've already

been using averted vision. Start

with a good quality pair of binoculars. 10 or 12 by 50s are ideal. You need

a reasonable objective lens size but you don't need huge magnification. That

just adds weight, and even a fairly lightweight pair of binoculars can feel

very heavy very quickly when you're looking up. If they're still uncomfortable

use a deck chair or sun lounger. Use them to look at large objects like the

Pleiades and the Andromeda Galaxy.

Start

with a good quality pair of binoculars. 10 or 12 by 50s are ideal. You need

a reasonable objective lens size but you don't need huge magnification. That

just adds weight, and even a fairly lightweight pair of binoculars can feel

very heavy very quickly when you're looking up. If they're still uncomfortable

use a deck chair or sun lounger. Use them to look at large objects like the

Pleiades and the Andromeda Galaxy.