Before we look at telescopes, let's look at the type of mount you might put it on.

Looking at the adverts in astronomy magazines, you could be forgiven for believing there is only one type of mount, and that's the one on the right. It's called an equatorial, and it's a very useful type of mount. It's aligned to celestial, rather than terrestrial, left and right and up and down. so it moves at an angle to our horizantal and vertical. It moves, therefore, in the same plane as the stars and planets we want to look at, so all you need to do is fit a motor drive to one axis and it'll track the object you're looking at. Fit a drive to the other axis as well and you can use it for astrophotography. As I said, very useful. But is it suitable for a beginner? Well, no, not really. Why not? Because every time it's moved it has to be aligned with Polaris, the Pole Star. That takes time. If you can't actually see Polaris it isn't possible. If it's a cloudy night but you desperately want to see something and you've got a few minutes between clouds you can't look at it, not with an equatorial mount. It's not a 'let's go outside and have a quick look at....' type of mount. Equatorial mounts probably run a close second to the British weather for putting people off astronomy, or at any rate for turning up at their local astronomical group saying 'I've bought this telescope and I can't find anything with it'. They're not that easy to use once they are set up, either - not when you have to consider whether the object's rising or setting and which side of the mount you need to telescope on, remembering not to walk into the counterweight, and that moving it to an object is not at all intuitive.

Of course if you can permanently site a telescope in an observatory of some sort......

The other two images are beginner's mounts. In fact they're both variations on the alt-az mount. Alt-az, or altitude-azimuth, means the mount swivels in the terrestrial horizantal and vertical. It won't track an object, but it requires no setting up. You can take it outside, put it down anywhere, put a telescope on it and start observing. Just what a beginner needs to stay interested. The object will drift across, and out of, the eyepiece, and you'll have to move the telescope slightly to put it back, but compared to setting up an equatorial it's child's play. But..... alt-az mounts are out of fashion. They're not the 'in' thing. Sad but true - just look in the magazines. You might find one, if you're very lucky and persistant. You might also find a 'Dobsonian'. It's not a telescope, it's the mount in the centre image. Originally home built from wood, the modern ones look a bit more sophisticated but essentially they're still an alt-az. Because the telescope sits low down, they can be very useful for the 'vertically challenged' viewer. Beware, though, of the small telescope on the Dobsonian mount. It could be uncomfortably low.

If the choice in mounts is somewhat limited, the choice of telescopes is bewildering, but we can once again break them down into some distinct types.

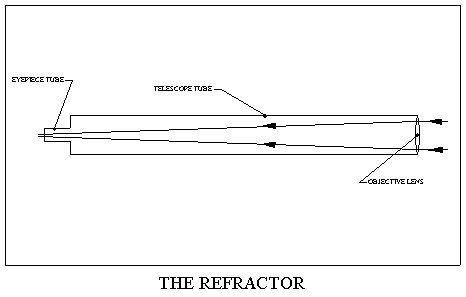

First,

there's Galileo's old refracter that does it with lenses. Large lenses free

from abberations are expensive to make but refractors come into their own for

planetary observing, where light is not an issue, but sharpness and image quality

are.

First,

there's Galileo's old refracter that does it with lenses. Large lenses free

from abberations are expensive to make but refractors come into their own for

planetary observing, where light is not an issue, but sharpness and image quality

are.

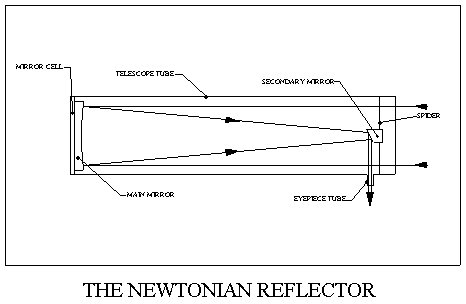

Then

there's Newton's reflector, which does it with mirrors. Mirrors are easier to

make than lenses and don't suffer the same abberations, so with a reflector

you get far more aperture for your money. This is what you want for observing

faint deep sky objects.

Then

there's Newton's reflector, which does it with mirrors. Mirrors are easier to

make than lenses and don't suffer the same abberations, so with a reflector

you get far more aperture for your money. This is what you want for observing

faint deep sky objects.

They're not so good for planetary observing because the central secondary mirror degrades the image, but if you want a good general purpose telescope then the reflector is it.

With any telescope it's possible to improve the sharpness of the image of bright objects like planets by using an aperture stop, which does just what it says - it makes the aperture smaller. On a refractor it prevents light passing through the outer parts of the lenses, which is where the worst of any abberations will be. On any telescope it changes the relationship between focal length and aperture - the focal length is the same but the aperture is smaller. The focal length is the distance the light travels between the first lens or mirror and your eye at the eyepiece. The longer the focal length relative to the aperture the sharper the image, which is why back in Messier's time, in the eighteenth century when astronomers were using almost exclusively refractors, they used telescopes of enormous length relative to their aperture. They had to because their optics were so poor. For anyone now using a reflector, the bigger the focal length to aperture relationship the better the telescope will be for planetary observing.

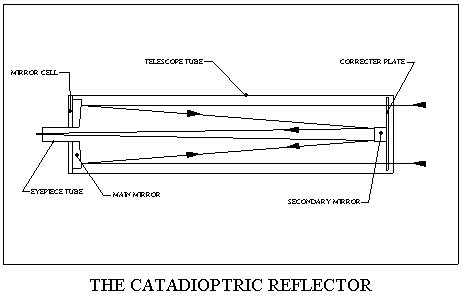

Then

there are the combination reflector types of telescope that attempt to combine

the best features of everything else and usually, at the same time, reduce the

tube length by folding the light path. Obviously they're more complex and expensive

than a simple Newtonian, but if you need a telescope that's compact and easily

transportable, this is probably what you'll be looking at. The most popular

is the Schmidt-Cassegrain, which as well as the short tube will also have the

eyepiece at the bottom like a refractor, which some people may find more comfortable.

Then

there are the combination reflector types of telescope that attempt to combine

the best features of everything else and usually, at the same time, reduce the

tube length by folding the light path. Obviously they're more complex and expensive

than a simple Newtonian, but if you need a telescope that's compact and easily

transportable, this is probably what you'll be looking at. The most popular

is the Schmidt-Cassegrain, which as well as the short tube will also have the

eyepiece at the bottom like a refractor, which some people may find more comfortable.

There are many other variations on these basic telescopes. Just about everything now has the 'go to' option. You can also buy add on computer controls for the more popular mounts. These are great if you're hosting something like a public viewing evening, if you're doing some kind of astrophotography when the aim is to record a good image, not spend hours looking for some obscure object, or if you merely see yourself as more of a technophile than a Charles Messier. There are little 'tabletop' telescopes which can be useful as a second 'scope, or to take on holiday. In fact telescopes come in many shapes and sizes. The shape must be the one that suits you, not the flash shop salesman. The size..... Well, the bigger the better, but it must be practical, again for you and not the person who sells it to you.

Any telescope that proves to be an expensive mistake will end up in the cupboard, or on Ebay, and you'll find your new hobby soon goes the same way, so my advice, old fashioned if you like, is:

Just go out in the dark and look up. Learn the brightest, easiest constellations for each season and you'll be able to find anything else.

Take a good pair of binoculars and look at star clusters and the Milky Way. Be amazed at just how much there is up there.

Get hold of the cheapest, simplest telescope of a reasonable size that you can buy, beg or borrow, get a copy of Messier's catalogue and start at the brightest and easiest, and be amazed at the beauty of what's up there.